Early Italian Renaissance Painting

|

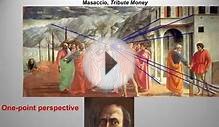

According to Alberti's system all parts of a picture have a rational relationship with each other and to the spectator, for the distance the latter is to stand from the painting is controlled by the artist when organizing his perspective construction. This system enables the microcosm of the painting and the world of the observer to become visually one, and the spectator participates, as it were, in what he observes. To fortify the illusion of a painting as a window on the world, quattrocento painters studied the effects of light in nature and how best to represent them in a picture, as well as human anatomy, and the world about them. These characteristics are essentially what separates early Renaissance painting from Late Gothic painting in Italy. Note: Much of the early work concerning the attribution of paintings was done by the art historian Bernard Berenson (1865-1959), who lived most of his life near Florence, and published a number of highly influential works on the Italian Renaissance across the country. Tommaso Masaccio (1401-1428) Not surprisingly, Masaccio is known as the father of Renaissance painting, for every major painter of the 15th and 16th centuries in Florence began by studying Masaccio's fresco painting. Masaccio is the artistic heir of the traditions of Giotto, yet there is no direct borrowing from the earlier master. Masaccio was also a friend of Brunelleschi who may have taught him perspective and how to create a rationally articulated space. He was also a friend of the Florentine sculptor Donatello (1386-1466) from whom he may have learned the effectiveness of simple drapery folds over a powerful figure. Whatever his creative resources, Masaccio's surviving work reveals a concern with simple figures clad in simple draperies. He was also occupied with light and how it gives the illusion of solidity to a painted figure. He created a clear and well-organized space in his paintings, and was above all concerned to create human characters carrying out some purposeful human activity. His only work that can be clearly dated is the Pisa Altarpiece of 1426 (of which the central panel portraying the Madonna enthroned with Christ Child and Angels, now hanging in the National Gallery, London, is the largest section). While Masaccio followed the medieval tradition of having a gold background, the architectural elements of the throne show an awareness of the influence of Ancient Rome. Furthermore, his Madonna is no longer a graceful heavenly queen but an earthly mother with a baby on her lap. The figure of the Christ Child is a clear demonstration of how light and shade can be manipulated in a painting to produce the illusion of a three-dimensional body. In this picture Masaccio laid the foundations for one major theme in Florentine painting. His focus on the sculpturally conceived figure, bathed in light and executed in a clear and simple manner, manages to produce a work of quiet dignity and great monumentality in that it appears to be larger than it really is. Masaccio's great series of Brancacci Chapel frescoes in the Church of Santa Maria del Carmine in Florence adds another dimension to early Renaissance art. In this narrative cycle on the life of St. Peter, he chose the most important point in the narrative and then captured the drama by laying bare the human reactions to it. In these works Masaccio also demonstrated his sense of the real world, for the light in the paintings, indicated by their shadows, is the same as the natural light falling onto the chapel walls. (1428) in Santa Maria Novella, Florence, effectively summarizes Masaccio's brief career as well as the aesthetics of early Renaissance painting. The sculpted figures have acquired even greater dignity. The drama of the work is presented in touching human terms as the Madonna turns to the observer to indicate her crucified Son. As well as using light to unite the space of the painting with the space of the spectator, Masaccio also uses what seems to be the earliest example of one-point perspective, later to be articulated by Alberti. All the exalted aims of Early Renaissance painting are present in this work: simplicity, strength, monumentality; man as observer, and participant. Masaccio had no immediate followers of equal stature, although there was a group of other Florentine artists of about the same age as Masaccio - namely, Fra Filippo Lippi, Fra Angelico, and Paolo Uccello - who followed in his footsteps to a greater or lesser extent. The innovative Sienese master Giovanni di Paolo (c.1400-82), noted for his small-scale religious panels, was another contemporary of Masaccio. Fra... |

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE

Share this Post

Related posts

Famous Italian Renaissance paintings

Leonardo da Vinci was regarded as an astonishing virtuoso, even by his contemporaries of the time. Born in 1452 he was at…

Read MoreEarly Italian Renaissance Artists

Greater Realism in Painting In keeping with the importance of Humanism, Early Renaissance painting strove to achieve greater…

Read More